by Rebekah Erway

With over 125 refugees arriving in Dayton, Ohio, in 2018 alone (according to Catholic Social Services), Cedarville students have a unique opportunity to minister to a disadvantaged group of people who live only 30 miles away.

Many students seem to be aware of this opportunity. Of those surveyed by Cedars, only two percent said they were unfamiliar with the global refugee crisis, and over 21 percent said they have been involved in refugee ministry during their time at Cedarville.

For the remainder, there seems, at initial glance, to be few opportunities for them to get involved with refugee ministries. Seventy-eight percent of students said their churches did not offer any kind of refugee ministry, and there are few ministries offered through Cedarville University. The Global Outreach office lists two available refugee ministries: King’s Kids and the Atlanta spring break mission trip.

And yet, not everyone can go on a spring break trip and some people aren’t comfortable working with children, so the two ministries may not be the right fit. Fortunately for such students, there are many refugee ministries available outside the Global Outreach office, with service opportunities beyond evangelism.

Students can find a refugee ministry to be involved in that fits a variety of different skill sets and still meets the needs of these disadvantaged people.

“The most effective way to minister to refugees is simply being available to help,” said Timothy Mattackal, in an email.

Mattackal, a senior finance and accounting major, volunteered with refugees in Atlanta on two spring break mission trips and over the summer. He said his time working in Atlanta has taught him that ministry to refugees is primarily relationship-based.

“Having good relationships with people and having them know that they can go to you for help in this difficult situation is one way that we can share God’s love with others,” he said.

One of the biggest mistakes Christians can make going into refugee ministry, Mattackal said, is viewing the group of refugees as a “monolith.”

“It can be easy to lose the humanity of individual people when using the term ‘refugee,’ so it is important to remember that everyone is an individual person with their own unique story,” he said.

Matthew Bennett, professor of theology and missions, agreed that refugee ministry is connected to relationships.

Bennett worked with displaced peoples in Jordan and Syria for several years before coming to Cedarville. His program focused on teaching English so refugees had an added skill to help them get a job and settle into society.

Bennett said part of sharing love with refugees includes giving them back a sense of dignity. When refugees come into the country, Bennett said, they leave behind their previous life, with its routines and recognized status. A Syrian who was a doctor in his country, once he is forced to flee, finds himself lumped together with the group of people known as “refugees.” Regardless of skill set, any refugee, once chased from home, no longer seems to have an identity beyond the refugee status.

Mattackal pointed out how the immigration process for refugees, especially in America, emphasizes the newcomers’ refugee status. Not only is the process of bringing a refugee to the U.S. intricate, Mattackal said, but so is the process of allowing the refugee to stay.

“Many of the people who have been resettled have had to live in refugee camps for years,” he said, “waiting for their applications to be processed and background checks and interviews to be completed.”

Bennett described how refugees can, at times, feel as though they are “just subsisting,” waiting in camps until they are displaced to another location where, like in the current one, they are simply “stored until people know what to do with [them].”

“There’s an objectifying that’s hard to escape,” Bennett said.

Refugees confront their own realities, often through intense questioning. Sometimes they question their previous country and religious systems, and other times, they question their very dignity.

“There’s a sense of a lot of loss,” Bennett said, “not merely on the physical, financial side of things, but even just that psychological ‘Who am I now?’”

Becoming a refugee dehumanizes people because it takes away their identity and leaves them with confusion and a lack of direction. Refugee ministry, therefore, Bennett said, must give the people skills and opportunities that would help them get back on their feet and regain their sense of self.

“[Give] them something that [allows] them to take steps down a path of restoring some sense of direction for their family,” Bennett said, “that they would be able to step out of this in between, transient status of being ‘refugee’ to being ‘employee’, to being someone who could define themselves other than by virtue of being displaced.”

While part of his ministry is giving people hands-on skills, Bennett said another important part is simply sharing the truth of where hope comes from. While he can help a refugee get a job or lose the refugee status, Bennett said that new job isn’t going to sufficiently satisfy the refugee’s need for orientation.

“[They] are still displaced,” Bennett said, “whether [they] have a home or not.”

Despite the many negative effects the displacements can have psychologically on the refugees, the time can also remove personal and cultural barriers to the gospel. As refugees question their lack of satisfaction found in their previous systems of religion and sources of identity, Bennett said his ministry tries to get them thinking about their identity as beyond the physical, immediate world.

“You can definitely see how the Lord redeems that time of being dislocated to being a time that is very pregnant with opportunity for meeting someone in a time of asking questions that they never realized they had to ask about the world they lived in and being able to provide the gospel as an answer,” Bennett said.

Gaining a sense of identity and belonging outside of their refugee label can be challenging. Since the refugees are in a foreign country with a new culture and different regulations, they can’t simply step out into society on their own.

Dr. Glen Duerr, associate professor of international studies, said that, too often, governments do not provide all of the resources to help these people re-orient themselves.

“A lot of Western countries don’t help refugees enough,” Duerr said. “What I mean by that is that they don’t bring citizens alongside them to help integrate them into society. They kind of have to fend for themselves and figure out a place to live.”

Churches and non-profit social services attempt to step in where the government leaves off by offering a variety of practical ministries to incorporate refugees into society.

One of the major services offered to refugees through these ministries are ESL classes. Often, refugees arrive speaking a language other than English, which adds a language barrier to their other difficulties in blending into society. Other important services for refugees, such as medical clinics, after-school programs, and job placement services, all become opportunities for ministry by meeting practical needs.

Refugee ministry, then, is three-fold: It must include the immediate help in form of food, housing and other supplies while they are in transient camps; the long-term help of providing practical skills and opportunities to get them back on their feet; and the spiritual help of answering their deep questions.

In face of this three-fold mission, refugee ministry can seem like an overwhelming task.“There are a lot of churches already who are doing that kind of ministry,” Bennett said. “There’s a lot of opportunity.”

Bennett recommended looking into Highland Baptist Church in the Columbus area for training and practical experience on working with Muslim refugees.

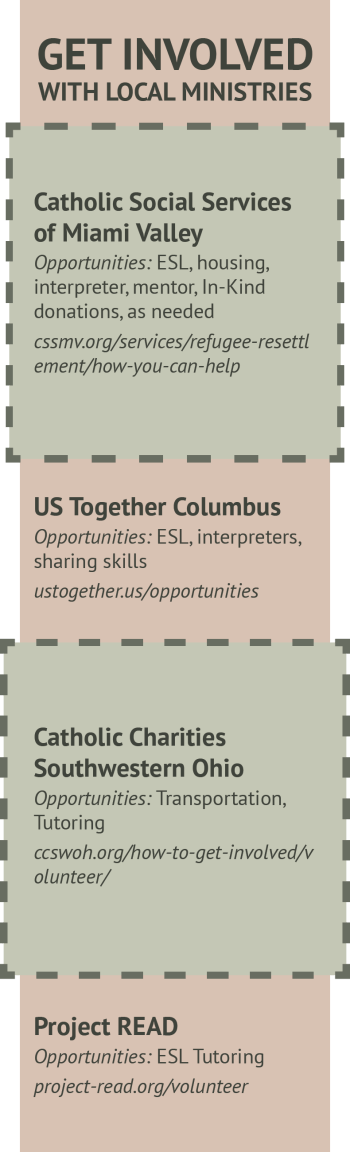

Mattackal mentioned volunteering with Catholic Social Services of Miami Valley, a refugee resettlement agency that is active in the Dayton area. While the Catholic Social Services are not a directly evangelical association, they partner with several area churches, including Christ the King Anglican Church. Opportunities to serve at the Catholic Social Services range from tutoring in ESL courses to cleaning out homes and preparing them for incoming refugees to donating personal and household supplies.

Students can also partner with refugees and minister to them by staying informed. Deurr recommended staying tuned to the international news and lobbying the government to help make foreign situations better so refugees don’t need to leave their homes in the first place.

“You have to look at why people are fleeing,” Duerr said.

Deurr said that students should pray over those negative situations and think about ways the government can step in and help those countries.

No matter how students choose to help, they can make an impact on the refugee crisis and share the love of Christ with, as Mattackal describes them, “some of the most disadvantaged people in society.”

“Being able to meet people in the midst of their need, in the midst of a whole new horizon of asking questions without the cultural pressures that have kept them form asking questions in the past, to be there to meet them with gospel answers is an incredible advantage,” Bennett said. “Someone is going to meet them with answers; shouldn’t it be the church, holding out the message of Jesus Christ and exhibiting a hospitality that is gospel-driven, gospel-shaped and gospel-saturated?”

Rebekah Erway is a senior Christian education major and Campus News editor for Cedars. She enjoys odd numbers, Oxford commas, and speaking in a British accent.

No Replies to "Ministering to the Sojourner in Our Land"